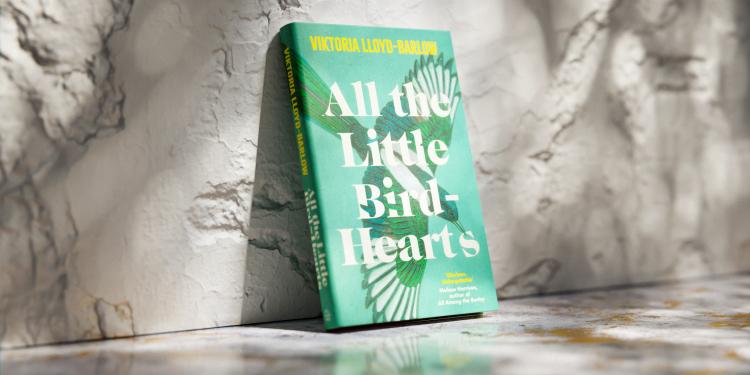

Interview

Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow’s lyrical and poignant debut novel offers a deft exploration of motherhood, vulnerability and the complexity of human relationships

Sunday Forrester does things more carefully than most people. On quiet days, she must eat only white foods. Her etiquette handbook guides her through confusing social situations, and to escape, she turns to her treasury of Sicilian folklore. The one thing very much out of her control is Dolly - her clever, headstrong daughter, now on the cusp of leaving home.

Into this carefully ordered world step Vita and Rollo, a charming couple who move in next door and proceed to deliciously break just about every rule in Sunday’s book. Soon they are in and out of each other’s homes, and Sunday feels loved and accepted as never before. But beneath Vita and Rollo’s polish lies something else, something darker. For Sunday has precisely what Vita has always wanted for herself: a daughter of her own.

The morning after our first meeting and shortly after Dolly left for school, Vita appeared at my door again. This time she was dressed in pyjamas. She did not reintroduce herself or apologise for the early visit. She moved easily, elegantly, through my hallway and into the kitchen, as if these visits were a routine between us. Her conversation was without preamble or introduction; she talked as if we were already in the middle of an ongoing discussion. It had been a long time since I had desired, or even allowed myself to believe in, the possibility of closeness with anyone. But I wanted it then, could feel the want beating like an excited little creature within me, rapid and rhythmic as a too-small heart.

‘Do you have milk? We have absolutely nothing in our fridge except wine. I am a terrible housewife. Rols always says he would starve in town without all the friends and restaurants.’ When she said ‘friends and restaurants’, she placed a hand on the outer side of each eye in a shielding motion and looked downwards, shaking her head slowly. It was as though she was emoting shame for a distant audience. Vita was extravagant and theatrical in all her expressions, and I appreciated that then. Her smile remained brilliant as she looked up at me winningly, hands still half-covering her large eyes. ‘What will he do up here?’

‘There is a café in town. And a Chinese. There’s a Chinese that does takeaways. You’ll like that,’ I said, intending to soothe her as I would have done with Dolly.

I repeated her phrasing silently to myself: no-thing in our fridge; ter-rible housewife; s-tarve without friends. It was unclear, as yet, how this seemingly random stressing on such words related to the content of her conversation. I naturally speak in a monotone, and Dolly sometimes imitated this, using an exaggeratedly robotic voice, which made us both laugh. ‘Good. Mor.Ning. Moth.Er,’ she would say in response to my flat greetings, her arms and legs moving stiffly as though she were fashioned of metal.

Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow

Vita’s claim to an empty fridge and wifely failure was not self-deprecating but congratulatory. I knew this because when I checked her face, she was smiling broadly, thrilled that she did not function like the other women on our street

Vita’s claim to an empty fridge and wifely failure was not self-deprecating but congratulatory. I knew this because when I checked her face, she was smiling broadly, thrilled that she did not function like the other women on our street. Vita’s face was open; she had the perfect combination of facial symmetry and a profound lack of interest in pleasing people. These factors made her face as seemingly easy to read as that of a child. This appearance of naturalness was, in fact, a construct, but a beautiful one. Her conversation, too, was appealing; I had not considered that our inability as wives might be celebrated. Edith Ogilvy believed that being a wife is the highest and most esteemed privilege of womanhood, although this had not been true for me. Vita sat at the kitchen table, leaning casually against the back of her chair as if she had been visiting me like this for years.

I did not know, then, that one could ask a neighbour to provide anything, especially if the lack of the item had been a matter of poor planning rather than emergency. Certainly, Edith’s book had never mentioned this. Vita yawned loudly as she watched me open the oversized white fridge that Dolly’s grandfather had gifted us the previous Christmas. He had been replacing the older-style display units in the shop with clear-fronted, square models that were edged in silver metal. I had been pleased with the gift, as I do not like to make such expensive purchases. I still have a considerable sum in my account, but I cannot earn such amounts of money myself. That summer, my inheritance was exactly half what it had originally been, and I still cannot tell when I would run out of money if I lived more extravagantly. I live now, as I did then, on the presumption that I have just enough. But that restraint was never the case where Dolly was concerned.

I handed my visitor a cold bottle of milk and she placed both hands around it, in that grateful and covetous way people sometimes have when given warm tea. She was not going home. She had the requested item, but she was still there, still talking. I sat down opposite her at the small Formica table that is one of the many relics from my parents’ marriage. I do not drink tea or coffee; Dolly had made those things for herself since she was very young. Vita would have to wait until she got back to her own house if that was what she wanted. She was wearing an Alice band and a pair of blue-striped pyjamas that had the navy initials ‘RJB’ monogrammed neatly over one breast. The fabric was of the thin summer sort that makes little effort to conceal what it apparently covers. I could see her chest rising and falling through the light fabric as she spoke, could see her small breasts shift, unfettered and soft.

I had never had a visitor in nightwear before, and was unsure whether her outfit would be on Edith’s list of Things That Must Not Be Mentioned, so I carefully did not. But when Vita casually compared her own dishevelled appearance to my plain and practical work uniform, it was me who blushed, as though my carefully observed omission was something more like a lie or a secret I was keeping. Vita had a scar that covered most of her hand, a silvery-pink covering like fish scales, which caught the light as her fingers moved across the bottle.

I remembered, as I often do, the fish that used to cover this kitchen when my parents were alive. The fish that were laid across every counter, opened up like trusting patients. During the tourist season, my father had taken holidaymakers out on his boat early each morning, and he brought the catches back to my mother to be prepared for the wives or landladies of these men to cook. Ma liked to watch for my father’s boat from her bedroom window, an early return reassuring her that the tourists were already satisfied.

Our little house had smelled permanently of the lake and the shining fish that shivered in my parents’ hands each day. Ma, self-taught, filleted and skinned as expertly as the local women knitted and sewed; her fingers came to know knives as theirs knew needles. Bones as delicate and white as baby teeth regularly littered our kitchen, as though it were the scene of a recent tragedy.

All the Little Bird-Hearts by Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow