Q&As with the 2021 nominated authors

Read our interviews with the nominated authors for this year’s Booker Prize

‘Fiction lets us summon imaginary lives we consent to care about as if they were real’

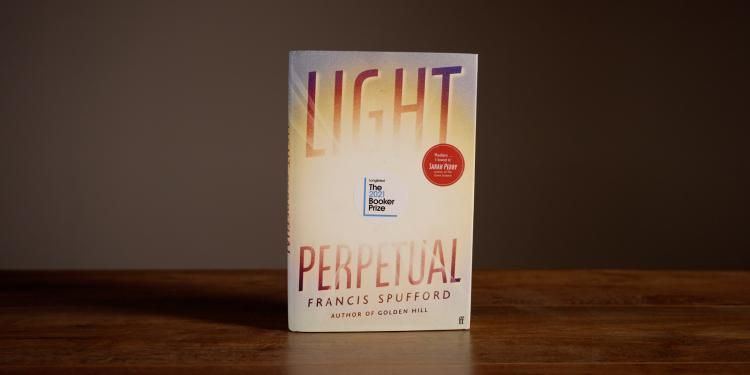

Francis Spufford speaks to us about the facts that inspired his Booker Prize-longlisted novel Light Perpetual, and his fascination with writing about time.

How does it feel to have Light Perpetual longlisted for the Booker?

Exciting and nerve-wracking. Also a kind of fairytale confirmation of my decision a few years back to move from non-fiction to fiction. Ah, so it *was* a good idea…

Which authors have influenced or inspired your own writing?

Michael Chabon. Zadie Smith. George Eliot. Penelope Fitzgerald. Alasdair Gray. Ursula Le Guin. And a thousand more.

What is your favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel?

Lately, a toss-up between The Luminaries (2013) and Lincoln in the Bardo (2017.) Further back, Possession (1990).

What are you working on next?

A plot-heavy noir detective story, with jazz soundtrack, set in the 1920s in a different version of American history.

Light Perpetual is partly a book about time: it opens with time slowing and continues with its alternates. It’s set in the past but also in the imagined future of its characters. Could you tell us a bit about your interest in time?

I’m old enough to have a memory that goes back nearly six decades, and to know intimately that everyone you meet in the present is dragging around an invisible comet’s tail of past selves. I wanted to write something that tried to do justice to the ordinary strangeness of our lives in time, using the blatant magnifications and contractions of time at the book’s opening to force a continuing greater awareness than usual of the texture of time itself going by in the passage of decades, days, the three structured minutes of a song.

You write that the inspiration for this story was a memorial to the victims of a wartime bombing. Can you describe the facts that led to your fiction?

On 25 November 1944 a German V2 rocket hit a branch of Woolworths in New Cross, South London. It was crowded with Saturday lunchtime shoppers, including a lot of mothers with toddlers who’d come out to get their hands on a delivery of new saucepans. 168 people were killed, including 33 children.

You’ve spent most of your writing life writing works of non-fiction. This book, your second novel, is not only fictional but also an evocation of what fiction is, or is for. Could you expand on this a little?

Fiction lets us summon imaginary lives we consent to care about as if they were real. In Light Perpetual, the imaginariness of the characters’ lives is under the extra pressure of them all being really (‘really’) dead. But I hope it makes you care more about them, not less.

It’s a memorial, but also not. Towards the end of the book one of your characters sees the site of the old Woolworths – bombed in the first chapter – from the top of a bus. In this version, it has been demolished by developers but her mind fills in the blank, so that it flickers ‘in and out of existence’. It – and she – would always have become dust eventually. Are you asking how much any of it matters?

I’m saying that lives matter palpably and self-evidently, and yet stand on a crumbling edge between existence and non-existence. We negotiate that combination of truths as best we can. Lost lives would have mattered just as palpably if they’d happened. In Light Perpetual, I’m not exploring the branching alternatives within lives, I’m trying to give human weight and volume to what never got a chance to happen at all.

Could you tell us about the presence of Catholicism in the book, its title and conception?

Anglicanism, not Catholicism. The prayer for the dead the title quotes is one that Anglicans and Catholics share. How does belief affect my writing? On one level, it’s engrained into my basic understanding – of human fallibility, of how lives get mended or don’t – which I think of as producing, not some kind of dogmatic distortion, but a more adventurous and open perception of whatever’s there to be seen. But on another level, as a matter of intellectual honour and specific artistic ambition, I’ve done my best to make sure the book works if you bring no faith to it all. It’s about the preciousness and fragility of our one life in time – what Philip Larkin called ‘the million-petalled flower of being here’ – and that’s something you feel equally, whether you think the alternative to time is eternity or nothingness.

Francis Spufford