The original Japanese title of the novel is 密やかな結晶 (Hisoyaka na Kesshō), which can be roughly translated as secret or quiet crystallisation, a translation we see reflected in the French title of the novel. Some have said the English title creates expectations of a political novel when its true meaning is more subtle. How did you (and the publishing team behind the novel) arrive at the title The Memory Police, and why was there a decision to focus on the antagonists rather than the psychological process at the heart of the novel?

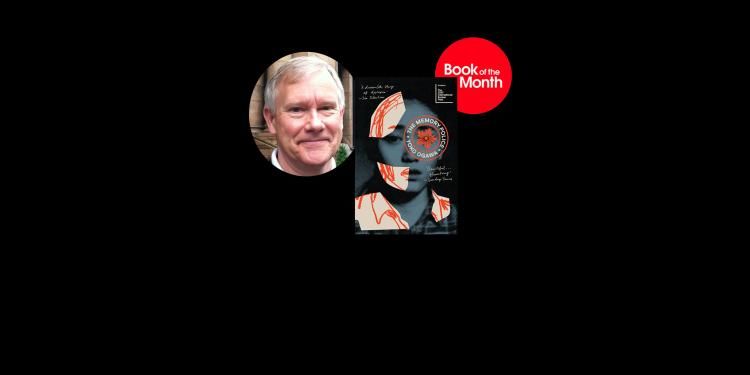

One of the very few adjustments I made in the translation is the one reflected in the title. The original text refers repeatedly to ‘secret police’ whose job it is to do ‘memory hunting’. For convenience and speed, I collapsed the two ideas, coining the term ‘Memory Police’. It was an editorial decision to use this term as the title, but one I support. I understand the change in emphasis, but I don’t believe the title masks the thematic content or creates expectations that aren’t borne out in the text. As we know, titles appear, context-free, before a reader encounters what lies between the covers, and their purpose (like the wonderful cover art for The Memory Police) is, in part, to bring readers to the experience of the work. In that sense, I think it’s clear that the new title was successful, in that it afforded a large number of readers that opportunity. Yoko Ogawa was consulted on the title change, of course, and approved of it.

As well as a translator, you are a Professor of Japanese Studies at Middlebury College and Dean of the Middlebury Language Schools. How did your work with the Japanese language begin, and how does the translation of fiction intersect with your academic work?

I started studying the Japanese language – out of a desire to read Yasunari Kawabata and others in the original – after undergraduate and graduate work in English literature. My original research in Japanese literature focused on the modern period – I wrote a book on Nagai Kafū – and narratological innovation during the rise of the novel in Japan. I was asked to translate Tsuji Kunio’s Azuchi Okanki (The Signore) while still a Ph.D. student, and have been translating contemporary fiction ever since. I have continued, off and on, with traditional literary research (and I dabble in translation studies), but translation has proved to be an enormously fulfilling aspect of my academic career and its major focus for many years.

Japanese literature is hugely popular in English-speaking countries. In 2022, titles translated from Japanese into English sold over 490,000 copies in the UK, making it the number-one original language for translated fiction sales in the country. What do you think is driving this boom?

The short answer, I believe, is simply ‘quality’ – both of the literature in Japanese itself and of the work being done by an excellent group of younger translators who are helping to drive this ‘boom’. Contemporary Japanese literature is the product of a long, rich tradition combined with a unique literary sensibility and a strong domestic reading culture. Japanese writers produce thousands of novels and stories each year, only a tiny fraction of which are translated into English or other languages. The winnowing process isn’t perfect, but translators and publishers have done a good job of selecting and promoting writers whose works resonate beyond the domestic market, and Japanese women writers, in particular, have found readers around the world in numbers disproportionate to the readership for translated literature in general.

Winners and shortlist mentions for this group from the International Booker Prize and, in the States, the National Book Award for Translated Literature (for the likes of Yoko Tawada, Yu Miri, Mieko Kawakami, and Yoko Ogawa) have helped a great deal as well. I used to argue that the extraordinary popularity of the works of Haruki Murakami gave an important boost to other contemporary Japanese writers, and his influence of course continues to be profound, but the reputations of and readerships for excellent writers such as Minae Mizumura, Sayaka Murata, Masatsugu Ono, Hiromi Kawakami, and numerous others suggest that Japanese literature has moved into a new phase of sustained creativity and global popularity that is extremely gratifying to see for those of us who have been observing the field for many years.